July 2025

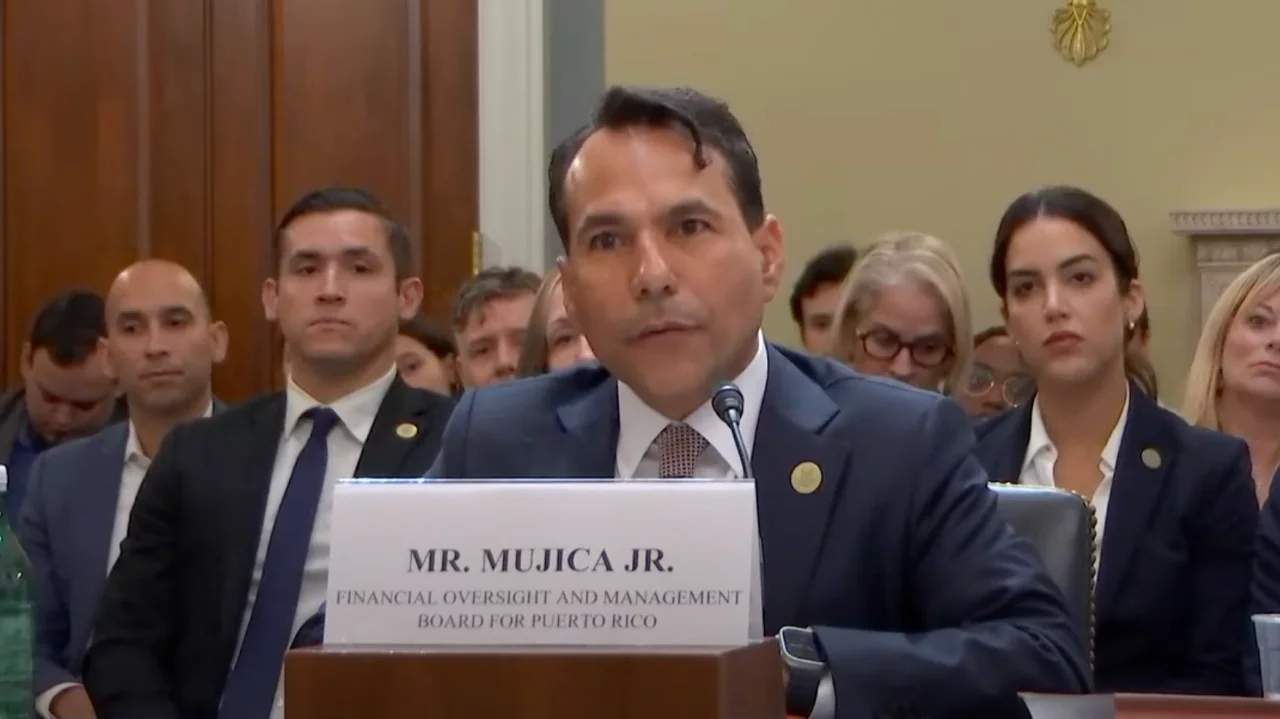

July 2 marks a solemn day: the eighth anniversary of the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority’s (PREPA) bankruptcy filing. Filing under Title III of PROMESA, PREPA and Fiscal Authority agents in 2017 expressed their confidence that this process would lead to continued operations and a successful restructuring. Notably, the filing came nearly three years after initial debt readjustment talks began between PREPA and its bondholders. Now, in 2025, the PREPA bankruptcy conversation has shifted from a $9 billion burden to a proposed $3.7 billion cash payment.

As News is My Business noted on April 25, paying the $3.7 billion out of PREPA’s $1.45 billion account balance requires “tapping into central government funds, raising electric rates and/or diverting funds meant for urgent grid repairs.” In other words, rates must go up.

On July 3, 2025, the Energy Bureau expects LUMA Energy, the private grid operator, to file a preliminary rate case, opening a full examination of how Puerto Rico’s power rate is set and how the new tariff will be built. Residents and businesses on the island should brace for sticker shock. The previous rate case, finalized in 2017, began in 2016, and relied on data from 2014.

Let’s briefly reflect on what has happened since 2014 to put that in perspective and highlight what a different world we inhabit over 11 years later.

-

The federal government passed PROMESA in 2016 to help the government restructure its blooming debt.

-

In May 2017, Puerto Rico filed for a special type of municipal bankruptcy with $72 billion in debt and $55 billion in unpaid pension obligations, the largest in US history.

-

In September 2017, Hurricanes Irma and María devastated the island.

-

In 2018, Puerto Rico’s legislature passed Act 120, which mandated private operators for PREPA’s operations.

-

Earthquakes in 2019 and early 2020 damaged infrastructure in the South.

-

In March 2020, COVID spread across the globe.

-

In June 2021, LUMA began work as the private operator of transmission and distribution.

And that doesn’t even mention the failed renewable energy procurement tranches, Genera, the FOMB, the mass outmigration, the PR100 study, future energy demand forecasts, and changes to renewable energy targets.

The point is: a lot has happened since 2014. Any reevaluation of the rate will consider fuel prices (Ukraine war, collapse of Iranian infrastructure, Trump’s “American Energy Dominance” policy), the cost of running the system, the waning customer base (outmigration, grid defectors), and future expectations of demand (energy efficiency, lack of non-federally-funded economic development, growth of EVs, etc.). Where will the chips fall?

LUMA is running a revenue shortfall of more than $136 million, as capital and operational expenditures outstrip power sales income. In May, they filed for an emergency rate increase to support these costs. The Energy Bureau denied the petition on technical grounds and sidestepped the hotly political issue of the definition of ‘emergency’. Meanwhile, residents may face power outages on nearly 90% of the days in July. Maybe I misunderstand what constitutes an emergency.

Come July, LUMA will file its explanation of the costs associated with operating Puerto Rico’s electrical grid. The costs are higher than what they take in. We’ll go through a six-month period for stakeholders to contribute to the conversation, but at the end of the day rates must go up.

-

If we’re able to get out of bankruptcy, rates must go up.

-

If we want more interconnection points for solar farms to become available, rates must go up.

-

If we want to access capital markets and attract power plant developers, rates must go up.

In 1924, Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon articulated what would later be known as the Laffer Curve in economics:

“It seems difficult for some to understand that high rates of taxation do not necessarily mean large revenue to the government, and that more revenue may often be obtained by lower rates.”

So yes, rates must go up. But does that solve the problem?

As I reflect on the need to cover operations and basic maintenance of an aging grid, it’s important to note that rates don’t need to stay up. Higher rates tomorrow do not mean higher rates forever. There are monumental efficiencies that can and will be achieved with responsibly planned capital investment and operational changes over the next decade, not to mention high-cost, big-ticket items that will roll off over time.

Perhaps this is the nugget of optimism that everybody should focus on: Puerto Rico can achieve system efficiency, operational cost reduction, and price stability. For the moment, though, rates must go up to achieve this.